(Illustration: Rafa Estrada)

안녕하세요 보스턴 임박사입니다.

제가 한국에서 신입사원으로 일하던 시기인 1990년대 중반에 대기업이었던 저희 회사는 주5.5 시간제를 채택하고 있었습니다. 즉, 토요일을 격주로 8시간을 일하는 것이었죠. 당시에 중학교 교사였던 아내는 주6시간제를 채택하고 있어서 토요일 가정일은 저의 몫이 되곤 했던 기억이 납니다.

시간이 지나서 이제 50대 중반에 접어든 지금 코로나 팬데믹 이후 재택근무 경험을 통해 주4일제 혹은 주4.5일제 근무에 대한 연구들이 진행되고 있습니다. 보스턴 지역의 회사들은 현재 모두 주5일제로 일하고 있고 특정 업무 분야에 따라 재택근무를 해오다가 최근 들어서는 그마저도 모두 오피스 근무형태로 하고 있어서 코로나 기간 몇년간을 제외하고는 주5일제를 하지 않은 적이 없다고 느껴집니다.

반면에 한국은 최근들어 주4일제 혹은 주4.5일제에 대한 뉴스가 많이 나오기 시작했는데요. 과연 어떻게 될지에 대해 궁금하기도 하면서 염려스러운 부분도 있습니다. 코로나 이전이던 2016년부터 최근까지 나온 주4일제와 관련한 뉴스기사들을 공유합니다. 주4일제에 대한 긍정적인 기사와 부정적인 기사를 함께 넣어서 가능한한 객관적인 시각을 담으려고 했고 관련한 연구논문도 첨부하여 보실 수 있게 했습니다.

주4일제에 대한 논의가 나오게 된 원인이 무엇일까?에 대한 저의 생각을 남기며 글을 마치고자 합니다.

코로나 팬데믹과 이후의 금융시장 환경이 인플레이션 압력을 받게 되었습니다 . 특히 청년세대인 MZ세대를 중심으로 한 FIRE Movement나 조용한 사직 (Quiet Resignation)과 같은 다양한 현상들이 나타났죠. 특히 신기술의 발달로 회사들이 앞다투어 채용을 늘리는 바람에 공고를 내놓고 1년 이상 뽑지 못하는 현상이 상당기간 나타났고 그로 인한 임금인상 압력이 다시 인플레이션에 영향을 주기 시작했습니다. 임금으로 인한 인플레이션은 고정비 성향이 강하기 때문에 기업 입장에서는 부담이었고 팬데믹 이후의 사무실 임대료도 상승을 했기 때문에 이러한 경향을 토대로 주4일제와 함께 임금을 다소 줄여야 겠다는 생각이 있었던 것이 아닐까 하고 생각합니다.

대부분의 회사가 팀단위 업무를 해야 경쟁력을 유지할 수 있는데 근무시간을 줄인다고 하면 팀 업무의 효율성이 늘기 보다는 줄어들 가능성도 꽤 있어 보입니다. 하지만 연구결과는 희한하게도 반대로 나오는군요. 그 연구결과에 참여한 기업의 수와 직원 표본의 수가 그리 크지 않기 때문에 그 결과를 곧이 곧대로 믿기는 어렵겠지만 특정 기업들의 경우에는 근로시간 단축이 곧바로 생산성 감소로 이어지지 않는다는 반증도 될 수 있을 것 같습니다.

생산성에 영향을 주는 것에는 노동과 투자가 있는데 투자가 잘 이루어지는 기업들의 경우는 노동이 생산성에 미치는 영향력이 미비할 수 있기도 하고 시스템이 잘 갖추어진 기업의 경우는 그렇지 못한 기업에 비해 개인에 의존하는 경향이 줄어들기도 하기 때문이죠.

몇가지 주4일제가 시행되게 되면 일어날 수 있는 문제점도 지적이 되었습니다. 예를 들면 나이든 노동자들의 임금이 상대적으로 줄어들게 될 수도 있고 정규직이 아닌 계약직의 업무 부담은 그대로이거나 늘어나는 대신 급여는 상대적으로 줄어들 수도 있을 것 같습니다. 그렇게 되면 정규직과 계약직 간의 임금 괴리현상이나 업무 강도 차이로 인한 소득 격차가 가중될 수도 있는 것 같습니다.

이제까지 직장생활에 임하면서 정규직과 계약직 그리고 지식산업을 하는 노동자와 육체노동을 하는 노동자 사이에 일어나는 상대적인 임금 격차, 워라벨 차이 및 나아가 노후준비에 대한 차이등으로 나타나는 경우를 보았습니다.

현재 아이슬란드나 덴마크, 노르웨이, 네델란드, 벨기에 등에서 주4일제를 많이 하고 있는 것 같습니다. 이런 국가들은 사회복지국가이고 투자기반이 강한 국가들이어서 개인의 노동 생산력 대비 투입자본의 투자 생산력이 더 중요한 생산성 증가 요소가 되는 국가들이라고 생각합니다.

1990년대 중반 이후 인터넷이 등장했지만 인터넷에 의한 수익성이 본격화되고 산업 재편이 된 것은 2020년대부터였던 것 같습니다. 요즈음은 AI/ML이 등장을 해서 인공지능 기술이 수익성 사업으로 본격화되기 시작하고 생산성의 중요한 요소를 인공지능이 차지할 수 있게된다면 주4일제를 하더라도 생산성의 하락이나 정체를 겪지 않을 수 있을 것 같습니다. 논의가 나오기 시작한 것이 얼마되지 않으니 지금부터 2-30년이 지나면서 서서히 자리잡지 않을까 하고 생각합니다.

Should Workers Over 40 Have Four-Day Weekends? – SHRM 7/26/2016

Research suggests shorter workweeks keep older employees sharp, productive.

If new research suggests that cutting the hours of older workers could boost productivity—and a company’s bottom line—should employers take heed?

While the prospect may sound outlandish, consider that Ford Motor Company founder Henry Ford was viewed as a radical—and was even called “crazy”—when in 1914 he doubled employees’ pay and reduced their work time from nine to eight hours a day.

Of course, Ford’s move didn’t apply just to older workers. Researchers recently claimed workers older than 40 are more productive when working around 25 hours a week because, the researchers said, a shorter workweek reduces stress and keeps them alert.

“Employers should not ignore any credible research that has implications for employee productivity,” said Jennifer Case, an attorney with Nelson Mullins Riley & Scarborough LLP in Atlanta, who weighed in on the researchers’ February study of more than 6,000 Australian workers. “Ford’s decision panned out and within a few years, Ford’s competitors made the same change. In more recent times, employers have responded to research that happier employers are more productive. Think Google and Facebook.”

The researchers, who published their findings in the Melbourne Institute’s Working Paper Series, studied about 3,500 women and 3,000 men in Australia, with various education levels, the majority of whom were between 40 and 69 years old.

The researchers wrote that working 25 to 30 hours had a positive effect on middle-aged and older men’s cognitive skills and reported similar results for older women working 22 to 27 hours. In other words, the research findings suggest that workers over 40 should enjoy four-day weekends each week to stay sharp and vigorous.

Benefits of Shorter Workweeks

While such a radical rethinking of the workweek seems implausible, the research raises compelling questions about the best ways to keep older Americans engaged and productive while on the job. At the same time, it raises equally compelling questions about equity in the workplace.

“I do think that a significant percentage of employees who think of themselves as near retirement would like to have the option of remaining employed with a reduced schedule,” said Shane Muñoz, an attorney with FordHarrison in Tampa, Fla. “Some are afraid to suggest that because they are concerned that their employer might question their commitment or their stamina. I think employers are also afraid to suggest it, for fear of creating an impression that they harbor stereotypical attitudes. Perhaps this study affords an opportunity for a more open dialogue on the subject.”

Some workplace consultants already recommend having employees work fewer hours to boost productivity, although not necessarily just for older employees.

“We recommend to our clients that they experiment with alternative schedules, flexible schedules and shorter working hours to see if it drives better outcomes,” said Bruce Tulgan, founder of management training firm RainmakerThinking, a management research, training and consulting firm in New Haven, Conn. “That experimentation should be done one person at a time. It makes sense to start with more experienced workers who already have a track record. Then it can be applied to newer workers.”

And some employers are already experimenting with shorter workweeks as a way to boost morale and productivity—although, again, not necessarily just for older workers.

“Employers are already taking a look at having fewer work hours for new hires, ” said Dan Schawbel, founder of Millennial Branding, a Gen Y research and management consulting firm, and author of Promote Yourself: The New Rules for Career Success (St. Martin’s Press, 2013). “They’ve done this to prevent burnout, increase employee satisfaction and remain competitive.”

Said Muñoz: “I certainly see clients who are open to considering accommodations for employees who prefer part-time schedules and situations where some measures of performance improve with reduced hours. I don’t expect, however, that well-advised employers will single out older workers, as a group, for reduced hours based on this study.”

And in some industries, longer-tenured employees enjoy shorter workweeks as a “rite of passage,” Schawbel said.

“As you gain authority in the financial world, it gives you more flexibility. A banker’s first two years are the most challenging and they are known to give up nearly all of their personal life to their companies as analysts. After the two-year mark, they are promoted and start to reclaim a more normal lifestyle.”

Dangers

There are risks, however, to considering shorter workweeks for older employees. For instance, it could make older workers vulnerable if such research becomes an argument for employers to give them part-time work with no benefits.

“You would essentially be creating a new category of employees that may consider themselves full-time but fall below the full-time threshold that exists today,” Case said. “For example, if they work less than 30 hours a week, then employers would not be required to make an offer of coverage in accordance with the Affordable Care Act.”

Moreover, if they worked fewer hours, older workers may be viewed as more expendable than younger ones, Schawbel said.

“The issue that many older workers have is the perception that they are less capable than younger workers, which is age discrimination, and that they are expensive, so many companies will lay them off and replace them with younger workers who will work for less [money].”

Discrimination and Resentment?

In general, it is not advisable to determine employees’ work schedules based on their age, Tulgan said.

Workers older than 40 are a protected class under federal law, he noted, “so employers need to be very careful.”

“It makes no sense to determine work conditions based on age,” he said. “The generational lens through which we can learn about the workforce tells us a lot, but we recommend against trying to have employment conditions, rewards or any such thing based on age or generation.”

Said Kris Duggan, CEO of BetterWorks, a goal-setting software and services provider in the San Francisco Bay area: “While there are some exceptions, like contract workers, requiring some employees to work less hours than others could create a backlash within your organization. Questions about compensation, employee evaluations and even bias from lack of face time will immediately surge.”

Millennial workplace advisor Lindsey Pollak of The Hartford, which offers property and casualty insurance, group benefits, and mutual funds, said that “year over year, The Hartford’s Millennial research has shown that a flexible schedule is incredibly important to Generation Y.”

In The Hartford’s most recent national survey, a majority or near-majority of Millennials said they want flexibility in the following: the timing of the workday, the days they work (weekdays vs. weekends), their amount of paid time off, where they work, and the number of hours they work.

Resentment aside, treating workers of one age group differently from those of another almost always opens a company to liability, Muñoz said.

“In today’s litigious environment, I absolutely would expect legal action, but I would expect it to come from those who aren’t given the opportunity to work a ‘full’ schedule based on an assumption that because they are over 40 years of age their productivity will drop off with extended hours.”

OXFORD: A group of companies that have been trialling a four-day working week have recently reported increased revenue, with fewer employees taking time off or resigning. While it’s easy to understand the effects of a shorter week on worker well-being, the positive effects on company earnings and productivity may be more of a surprise – but research backs this up.

These firms have been participating in a trial organised by non-profit 4 Day Week Global. The four-day working week trial, which involved 33 companies and nearly 1,000 employees, saw no loss of pay for employees – organisations paid 100 per cent of their salaries for 80 per cent of their time. But employees also pledged to put in 100 per cent of their usual effort over the shorter working week. And this kind of strategy doesn’t just work for nine-to-five office jobs.

Iceland trialled reduced working hours between 2015 and 2019 in a scheme that included hospitals, schools and social service workers. The country considered it an “overwhelming success” and reduced hours – without a reduction in pay – has since been rolled out to 86 per cent of Iceland’s workforce.

Throughout history, our working patterns have adapted to the challenges of the day: Whether that be more time toiling at an industrial loom, or a farmer shifting their hours to eke out productivity during fading daylight hours.

But now, almost a century on from Henry Ford introducing the two-day “weekend” to his factories, many nations are still stuck with a 40-hour week split across five days of work, regardless of the industry. This way of working is increasingly at odds with our 21st-century lifestyles.

The latest findings from the 4-Day Week Global pilot are in line with ongoing research into working patterns that show reduced hours boost employees’ mental health and their productivity. It also brings other benefits such as reducing emissions by cutting commutes and providing the basis for evaluating our lives in more than just monetary terms.

HUGE INCREASES IN STRESS AND BURNOUT

Despite much economic growth since the 1970s, very little progress has been made on freeing up time for workers. Worse, in some cases, the trend has started going in reverse: Americans now work more hours than they did in 2000, for example.

That is starting to take its toll on employee well-being and mental health. It doesn’t take much to realise that becoming many times more productive over the past century (thanks in no small part to technology) means our human brains are being asked to process a lot more during a five-day work week than in the past. This has led to huge increases in stress, anxiety and burnout.

This is hitting national health services and families particularly hard. But employers are also bearing the cost: Accountancy firm Deloitte estimated the annual cost to employers of mental health issues is £45 billion (US$55 billion) in the United Kingdom alone. This is mostly due to absenteeism, or worse “presenteeism” – where a person is physically present at work but not engaged because they feel ill.

The UK’s Office for National Statistics estimates that there were 17 million worker days lost to stress, depression or anxiety in the UK in the period of 2021 and 2022. And the same trends show up for most other wealthy countries.

FEWER HOURS, INCREASED PRODUCTIVITY

Of course, company bosses might think: “If my employees are working 20 per cent less time, surely output will drop, too?”

But several studies have shown that is not the case. In fact, countries doing the least hours of work are often the most productive on an hourly basis.

These countries, such as Denmark, Norway and the Netherlands, are also the happiest. All work less than 1,400 hours a year on average, compared with the US and UK average of about 1,800 hours.

My own research, in collaboration with British Telecom, helps explain why working less hours doesn’t necessarily mean an equivalent loss in output. We were able to show the positive effect of feeling better during the week on weekly productivity. We found evidence of more sales and more calls per hour when workers were happy.

Based on our research, we believe the work-life balance changes and improvements in well-being coming out of the 4 Day Week pilots could lead to an increase in productivity of about 10 per cent.

Of course, a 10 per cent increase in individual productivity will not immediately make up for employees working a day less. But these productivity gains would reduce the cost of a transition to a shorter work week.

So there might still be a need for investment and subsidies from government and business alike to support this change, but people and the planet have much to gain from doing so.

TIME, OUR MOST PRECIOUS COMMODITY

It’s also important to think more holistically about the benefits of the four-day week beyond productivity and well-being.

A shorter week might even reduce the UK’s carbon footprint by cutting commuting – assuming that most people won’t travel or will travel significantly less on their day off. A four-day week could have a positive effect on gender equality as well, since the pilots suggest that women report the largest increases in well-being.

The four-day week debate also scratches the surface of an ongoing discussion among economists. Gross domestic product has long been used as the ultimate measure of a nation’s progress, often with the effect of seeing policymakers chase growth at any cost. But a country is much more than its gross domestic product.

Seeing the successful results of attempts to implement a four-day working week might convince business and policy leaders to redistribute some of the gains in GDP in terms of our most precious commodity: Our time. Now that could be considered real progress.

Jan-Emmanuel De Neve is an economist and professor at Oxford University where he directs the Wellbeing Research Centre. This commentary first appeared on The Conversation.

How to Actually Execute a 4-Day Workweek – Harvard Business Review 12/8/2023

Coming out of the pandemic, the conversation about flexible work has largely focused on whether employees should return to the office — and how often. A third of U.S. workers who can do their jobs remotely now do so all the time. LinkedIn research shows that in May 2023, nearly one in nine U.S. job postings offered remote work, 13% of postings were hybrid, and 66% of applications were for remote and hybrid roles. A CEO told me that by putting the word “remote or hybrid” into the job description, the number of job applicants tripled.

But a potential new disruption looms: We’re starting to hear from organizations that have piloted a four-day workweek. Early results suggest this structure offers benefits in productivity and well-being.

Let’s look at the evidence. According to research from jobs platform Indeed, while the overall number of job posts advertising a four-day workweek remains low (0.3% of total posts), that number has tripled in the last few years. And it’s most commonly seen in sectors requiring in-person work, such as medical, dental, veterinary, manufacturing, and production. United Auto Workers initially included a four-day workweek in its bargaining demands, although this provision wasn’t included in the final agreements.

In June 2022, 61 UK-based companies participated in a pilot program to study a four-day workweek. As of February 2023, when the first results were published, 92% said they were continuing to test the concept, with 29% saying the policy is a permanent change. Average organizational revenue rose by 1.4%; pilot companies also reported a 57% decline in the likelihood that an employee would quit, plus a 65% reduction in the number of days taken off as paid sick time.

One of the trial participants was Rivelin Robotics. The firm opted to close on Fridays and extend the working day to 8 am to 5:30 pm on the other days of the week. The change has not been without its challenges. A small, fast-growing startup with just eight staff, Rivelin reports that sometimes the work cannot wait, and a big product launch meant some of the new three-day weekends had to be sacrificed. Senior execs had to accept they’d take Friday calls and queries, as the team had turned off their phones.

The Challenges of a Four-Day Workweek

In the 1960s and 1970s, a number of organizations sought to implement four-day workweeks. Unfortunately, most of these initiatives — which attempted to condense a full 40 hours of work into four days — didn’t see the results that organizations had hoped for. One 1975 study surveyed the reactions of 474 employees of an accounting division of a large multinational corporation to a four-day, 38-hour workweek. Fatigue and slowing down at the end of the day were reported, and servicing of customer needs and meeting with co-workers were more difficult. Supervisors perceived that work quality and output in their units were adversely affected by the four-day workweek.

Looking back, we can see how these initiatives failed to consider a few critical factors. First, there is a non-linear relationship between hours worked and productivity; there is a diminishing rate of productivity for each additional hour someone works. Longer working hours also are associated with increases in errors and work injuries, as well as decreases in employee well-being indicators like satisfaction and engagement.

But who says you have to do 40 hours in four days? There’s a growing body of evidence suggesting that reduced-hour work schedules for the same level of pay are not only feasible when it comes to maintaining outcomes but also potentially advantageous across a number of metrics. Since 2015, a new, more data-informed wave of reduced working week trials have now been conducted in growing numbers in Sweden, Ireland, North America, the UK, and Australasia. We also recently worked on our own study of nine global organizations to deepen our own understanding of the practicalities of conscious work redesign. We found that although there were some costs, trade-offs, and varying levels of work involved to prepare for a four-day workweek, the results were consistently positive when it came to things like employee well-being, retention, and even business outcomes.

These initiatives only work if companies undertake substantial work redesign to reduce hours while maintaining business outcomes. This means streamlining operations, removing administrative burdens, and prioritizing high-impact work. To achieve this, our study suggests organizations need to:

Clearly define the work that matters.

Frameworks such as OKRs (objectives and key results) can define company and team-level goals and ensure everyone’s work ladders up into those goals.

Run a meeting audit.

Meetings are often one of the first areas to get scrutinized as unproductive time.

Allow employees to operate to the full extent of their education and training.

Many employees are bogged down with other administrative or menial tasks, so they can’t focus on priority tasks. We recommend stopping, automating, or outsourcing all non-priority tasks.

Embrace asynchronous communication.

When implementing a four-day workweek, asynchronous communication becomes essential to help employees from having work interrupted. To maintain employee focus, there should be a clear understanding of what requires escalation, and who will handle it.

Resetting Employee Expectations

One major challenge that accompanies the shift to a four-day workweek is ensuring employees accept that you’re asking them to produce the same amount in fewer hours. Our own research shows organizations that successfully implemented a four-day workweek began with a well-defined three-month trial period at a minimum to assess whether they could successfully reduce work time while maintaining output. These pilots included documentation, and/or training in advance for employees on redesigning work tasks, as well as productivity coaching. (What’s interesting is that even just doing this prep to streamline operations, remove administrative burdens, and prioritize high-impact work can improve company productivity substantially.)

What does this look like in action? As part of our research project, we spoke to a workplace consultancy in Australia called Inventium that started a four-day pilot in 2020. Its leadership developed productivity training to help employees more effectively utilize their time. Tactics included calendar blocking, turning cell phones off for blocks of time, and scheduling deep work around when each employee is most productive.

At Inventium, employees are encouraged to take ownership of their time and utilize it in the way that works best for them. It seems to have worked, as the company reported a 26% increase in productivity, a 21% increase in energy levels, and an 18% decrease in employee stress.

The company refers to its program as the “gift of the 5th” — highlighting that the day off is not a given. Instead, it’s achieved by getting work done efficiently and maintaining outcomes. It also signals that there may be busier months when employees need to work that 5th day, which has now been cheerfully (so far) accepted by the entire team.

To ensure success, organizations need buy-in from leadership and employees. You can start by crowdsourcing potential obstacles and ideas from employees. It’s also critical to position the pilot as an experiment with clear expectations and to be transparent with clients and external stakeholders.

The four-day week can surface organizational problems in communication, trust, work inefficiencies, and barriers to productivity. And while it provides an opportunity to address these challenges, as Joe O’Connor, director and co-founder at the Work Time Reduction Center of Excellence and one of our co-researchers warns, “This is not a cheap fix, it’s very hard work.”

In today’s economy, employees have more power, agency, and freedom than ever. Unemployment reached a 54-year low this year, wages are increasing (5% annually), and open posts are very hard to fill. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce says even if every unemployed person in the country found a job, the U.S. would still have around 3 million open positions. And the worker shortage is likely to go on for years.

In today’s competitive labor market, where attracting and retaining top talent is an ongoing challenge, adopting a reduced-hour workweek can be an attractive benefit for job seekers — and could be a significant competitive advantage for recruitment teams. And for everyone else, it’s an opportunity to really get focused on what matters.

Readers Also Viewed These Items

- Threadless: The Business of Community (Multimedia Case)ToolBuy Now

- Bridgewater Associates (Multimedia Case)ToolBuy Now

Read more on Work environments or related topics Business management, Human resource management and Flex time

- Josh Bersin is founder and CEO of human capital advisory firm The Josh Bersin Company. He is a global research analyst, public speaker, and writer on the topics of corporate human resources, talent management, recruiting, leadership, technology, and the intersection between work and life.

There’s no magic in a 4-day workweek – The Hill 1/12/2024

The idea of a four-day workweek is catching attention. Young workers in particular see it as the wave of the future, while others worry it will undermine America prosperity.

Economists have pondered the viability of a four-day workweek since research by Janice Hedges in 1971. Recently, though, a magical idea has come to the fore: Let employees work one fewer day per week at the same hours per day and same pay, and they will accomplish just as much as in a standard five-day workweek.

All the fuss prompted us to ask several hundred American business executives and several thousand American workers some pertinent questions. What we uncovered is mundane, not magical. In the language of “Harry Potter,” there is support for a “muggle” version of the four-day workweek — but not for a magical one.

In October, we asked 602 senior managers across the U.S. whether their firms offer a four-day workweek to any full-time employees, and 20 percent said yes. For those who said yes, we also asked what share of their full-time employees work a four-day week — on average, 25 percent. So about 5 percent of full-time American employees currently work a four-day week.

Is the U.S. on the cusp of a big shift to four-day workweeks? No. Of the 482 managers at firms that don’t currently offer four-day workweeks, two-thirds said there is no chance their firms will offer them by the end of 2024. The other one-third say the chances are only 16 percent, on average.

In practice, there are several versions of the four-day workweek. One involves fewer but longer workdays, with no change in weekly hours. Another cuts the number of workdays without changing the length of each workday, but recognizes that fewer hours means less output and thus lower pay. Yet another version lets employees work from home on Fridays (or Mondays) but work onsite the other four days.

We think of these variants as “muggle” versions of the four-day workweek, because they recognize the reality that output and pay are roughly proportional to time spent working.

Then there is the magical version: Let full-time employees work eight hours a day, four days a week rather than five — with no reduction in output or pay.

Keep an open mind, you say?

Consider some evidence. We asked managers at firms that currently allow four-day workweeks how many hours their full-time employees put into their jobs on those four days. The average is 9.5 hours. Just 22 percent of managers said their full-time, four-day workweek employees put in eight or fewer hours on their workdays. More than 75 percent of managers told us that some or all of their employees on a four-day workweek are expected to be available for work on “off days.”

In short, managers don’t see the magic.

But even with no magic, four-day workweeks can be beneficial. If your daily commute is 30 minutes each way, muggle versions of the four-day workweek save one hour a week. This also saves on the money costs of commuting, not to mention the aggravations of traffic jams and public transit.

To assess these benefits, we turned to our Survey of Working Arrangements and Attitudes, which samples thousands of American workers each month. In October, we asked survey participants who usually work five days a week whether they would prefer to work the same weekly hours over four days. Nearly 60 percent said yes. They also said shifting to a four-day workweek was worth as much, on average, as a 4 percent pay hike.

Employers can also benefit from muggle versions of the four-day workweek. For example, they can offer smaller pay raises in exchange for less commuting, perhaps by letting employees work from home one day a week. This arrangement also reduces office floorspace requirements, lowering overhead costs.

Sadly, we must live in the real world, not the world of wizards. It’s time to set aside the distractions of magical four-day workweek proposals. Happily, even realistic four-day workweek schedules can benefit both employees and their employers.

Jose Maria Barrero is assistant professor of finance at Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México Business School. Steven J. Davis is a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution. This piece draws on research with Nick Bloom, Kevin Foster, Brent Meyer and Emil Mihaylov.

Why Germany is launching a six-month trial of 4-day work week from Feb 1 – The Economic Times 1/28/2024

Germany’s struggle to revive its sluggish economy is about to take an experimental turn as a host of companies test out the merits of working less. A six-month program starting Feb. 1 will grant a day off every week for hundreds of employees while keeping them on full pay. The study aims to find out if labor unions are right that it could not only leave staff healthier and happier, but also more productive.

“I’m absolutely convinced that investments in ‘new work’ pay off because they increase well-being and motivation, subsequently increasing efficiency,” said Sören Fricke, co-founder of event planner Solidsense, one of 45 companies taking part in the pilot. “The four-day week, if it works, won’t cost us anything either in the long run.”

The project underscores a broader shift taking place in the German labor market, where a lack of skilled workers is putting pressure on companies to fill their ranks. The shortage — coupled with high inflation — has emboldened employees across industries to seek wage increases and preserve the flexibility and independence they gained during the pandemic. About 45 companies in Germany will trial a four-day work week to measure any productivity gains from working fewer hours.

The imbalance is fueling employer-employee tensions. Germany’s train drivers are currently holding a six-day strike, demanding that Deutsche Bahn cut the work week to 35 hours from 38 hours without any wage reduction. The country’s construction union is asking for a pay rise of more than 20% for many of its 930,000 workers — a move some economists warn could stoke inflation.

According to an industry lobby survey last year, half of German companies are at least partly unable to plug vacancies. Software giant SAP SE stopped asking for university degrees from applicants in 2022, while real estate firm Vonovia SE recruited people from Colombia last year to cope with the shortage.

And the problem is set to get worse: more than 7 million people are expected to leave the German labor force by 2035, as birthrates and immigration fall well short of what’s needed to replace the aging population.

“I can either get involved and position myself as a modern company, or I can say that we all have to work more and at some point I won’t have anyone left to work for me,” said Henning Roeper, managing director of Eurolam, a Wiegendorf-based window maker that’s also taking part in the program.

And unhappy workers come at a hefty price tag. According to a recent Gallup study, low engagement costs the global economy €8.1 trillion ($8.8 trillion) last year. That’s 9% of global gross domestic product.

While staff work fewer hours during the experiment for the same pay, their output should stay steady — or even increase, according to New Zealand-based non-profit 4 Day Week Global, which is leading the pilot. Aside from that boost in productivity, companies are also expected to benefit from a drop in costly absences due to stress, illness and burnout. The average 21.3 days Germans were incapable to work in 2022 meant a loss of a staggering €207 billion in value added, according to the Federal Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

Advocates of the four-day week also argue it could attract untapped potential to the labor market in Germany — a country that has one of the highest proportions of part-timers in the EU, also among women, according to Eurostat.

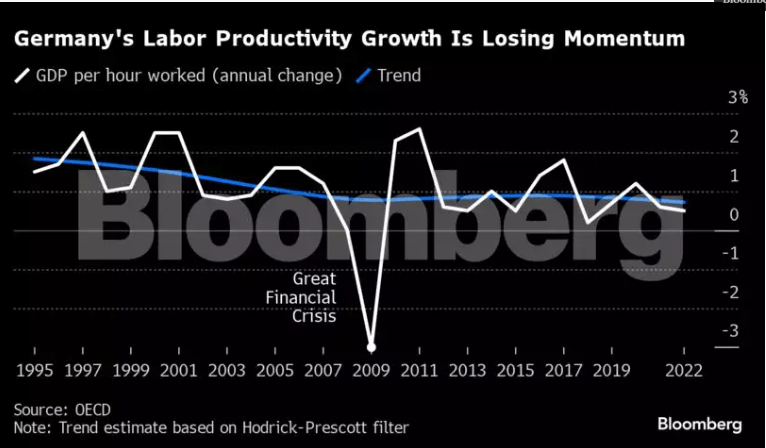

While Germany has by far the biggest economic output in Europe, a lack of investment in innovation and digitization has hindered productivity gains. Without improvements in those areas, it’s unlikely German workers would see a significant productivity boost simply by cutting back hours, according to Enzo Weber, an economist at the Institute for Labor Market Research in Nuremberg.

Finance Minister Christian Lindner, a member of the business friendly Free Democrats Party, has offered more pointed criticism of the shorter week, saying such a move would threaten economic growth and German prosperity.

But previous experiments in the US and Canada suggest gains are possible, according to 4 Day Week Global. Workers who took part reported improved physical and mental health while burnout dropped. Following the studies, none of the participating companies planned to return to a five-day week.

A program in the UK, the biggest one yet with 61 participating companies, showed similar gains, including a 65% drop in sick days. In Portugal, anxiety levels and sleeping problems receded by roughly 20%. The German companies are hoping for similar gains, and some participating workers plan to provide hair samples and data from fitness watches to track stress levels more accurately.

“If I have too much time I become a perfectionist, and this is not always necessary,” said Jasmin Galle, a user-experience designer at Solidsense. “If you have less time, you still get the same result.”

Belgium became the first European country to make a 4-day-week optional in 2022, though the total weekly hours must remain the same as in a five-day week. Japan has encouraged companies to offer shorter work weeks in hopes people will use the time to spend money and have children, boosting its economy and aging population.

Jan Bühren, co-founder of Intraprenör, a Berlin consultancy working with 4 Day Week Global on the pilot program, said achieving the gains requires flexibility and creativity at the companies.

“Of course it doesn’t always work and it’s also not for everyone,” he said. “But you just have to find out exactly where it can work and where it doesn’t.”

What Bloomberg Economics Says…

“A four-day week could lead to higher hourly productivity but it’s very unlikely that a productivity boost can compensate for the reduced working hours. Together with a shrinking labor force this would be a major obstacle to economic growth.” — Martin Ademmer